Blogs of Team Energy Poverty

By Youssef, Ethan & Casper

Minor: Global Crisis, Local Challenges

Blog 1: The beginning

8-9-2023

Part A: Brainstorming

Team Energy Poverty was formed in the last minutes of the Wednesday lesson and as such, did not do significant amounts of brainstorming beyond post-it notes. Nonetheless, the group has been able to identify several directions for the Big Idea. More importantly perhaps, Team Energy met again on Thursday to get to know each other, recap the lessons learned on Wednesday and prepare the first blog. Finally, also scheduling a meeting for next week Monday to fully kick off the Project component of the Minor.

One of the first questions that we asked ourselves was why we chose this topic, what attracted us to Energy Poverty. Youssef mentioned that he relates to it himself, as many of the poorer citizens in Egypt have little access to energy due to the infrastructure and costs. He also mentioned the unfair accessibility to energy as a possible topic. Ethan recognized this and was also interested in this injustice component, as well as the social economical effect of energy poverty in the Netherlands. Casper chose for the topic because it is a hot topic in the Netherlands with the energy transition, and believes that the struggle to get everyone into renewable energy and well-isolated houses cannot be done without spending attention on energy poverty. Then, we looked at our academic profiles and found that we have quite a balanced group for this topic, as Youssef studies Industrial Design, while Ethan has experience with sustainable transitions and Casper profile focuses on (environmental) policy and management.

The rest of the brainstorming followed the post-it format, which means that we currently mostly have some abstract ideas and connections. One important conclusion though was that we needed the know what Energy Poverty was before we chose our Big Idea. Our findings can be found in Part C of this blog. The remaining discussion centered mostly around two ideas. The first was in the direction of changing energy sources, for example with the hydrogen transition. Here it was also mentioned that the Netherlands is still dependent on foreign powers for energy (Russia, USA, Norway, as well as that changing to renewable energy is expensive and subsidies often aren’t used for the people that need them most. In comparison, the other train of thought was related to the idea that energy prices will keep increasing, so poor people will keep struggling with energy costs. One idea following that was the reduction of energy consumption, for example through isolation of housing, energy budgets and recycling.

Part B: Challenge Based Learning

We face challenges everyday. Some are physical and some are mental. Some are tough and some are easy. Some appear out of nowhere and some are created by us. All in all, challenges have become a norm in our daily lives and they require a solution otherwise they will remain a problem that will have bad impacts on us and on others. How we look at the challenge itself and how we solve it is what defines us. Each one of us has his or her own perspective on the challenge as well as their own skills, experiences, and techniques on how to solve a certain challenge.

Challenge based learning (CBL) is a process where one is encouraged to tackle a problem through engaging with it, then investigating it, and finally acting upon a solution. A person is taught not by being told what the solution is but by trial and error and using past experiences and external sources to identify the correct solution to a problem. The complexity of the challenge generally requires an interdisciplinary approach to solve, and together with the teamwork and relatively short time frame, CBL often becomes a pressure cooker for students. Consequently, they are able to develop not only their knowledge on a specific topic, but also many skills, such as problem solving, critical thinking, and teamwork. In addition, CBL can create environments that support proactiveness and communication with people that have different expertise's.

The main difference between challenge based learning and “normal” learning that could be found in schools is that with challenge based learning I feel that students really own the problem and make it theirs to solve. Also the solution is a mystery and depends on the team's skills and perspectives to result in a unique solution. Another person or group taking on the same challenge might come up with something totally different, yet they both might work, and they both could be good solutions. Finally, CBL students get to learn through failure. Normal education often involves much more set boundaries and frameworks to work in, as well as there being often only 1 real solution. There are only so many ways one can model a teacup after all. There is not much freedom to tackle the problem such that it results in unique solutions that all work just as good.

Part C: The Big Idea

To determine a challenge for this minor our team has chosen to focus on the big idea of Energy Poverty. This form of poverty has multiple definitions that depend on the context of the problem. For instance the UN has defined Energy Poverty as a lack of access to modern energy services. This includes an accessible, affordable and reliable energy supply and the appliances to use this energy to improve the well-being of humans (UNDP, 2005; UNDP, 2010). Using this definition, we can see that about 789 million individuals are still lacking access to electricity. This number, however, is decreasing exponentially. Although there are still 2.8 Billion people that need access to clean and safe cooking fuel and technologies (United Nations, 2020). The European Commission has defined the idea in the context of the EU and its 'Developed' society. They state that 'Energy poverty occurs when energy bills represent a high percentage of consumers’ income, or when they must reduce their household's energy consumption to a degree that negatively impacts their health and well-being.' This definition stems from the energy crisis Europe is being confronted with as a result of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the reduction of oil imports from Russia since the start of the Russian-Ukraine War.

While the EU's definition of Energy Poverty only differs in the details and in essence would fall under the definition set by the UN, the fact that Europe already has access to modern energy services makes the issue more specific to the situation that a household cannot maintain the services that they have access to due to the high prices and their social-economic position. In fact, similar descriptions of energy poverty have also been used in the Netherlands by Parliament members, so the EU definition has been used in Dutch context.

If we now look at the global crises that we looked at in the first two classes of this week, then we see that energy and specifically the way we make energy puts pressure on the planet to support these activities. An example is the climate crisis that is mainly driven by the emission of greenhouse gasses that disrupt the balance of our planet affecting many abiotic factors (e.g., temperature, precipitation) that are important to maintaining the planet and the life that makes it its home. Another example is the Land system change and biodiversity. To acquire materials such as metals, minerals and non-renewable energy sources, large amounts of Energy and water and toxic chemicals are required for the extraction process (UNEP, 2020). This can disrupt many habitats, compromise freshwater sources and pollute the land making these areas unsuitable for life to exist and nature to maintain balance.

Energy poverty is as much an environmental as a social-economic and technical problem that requires a variety of actions in order to mitigate it. By involving parties from the local area such as the municipality, consumers and producers we could find solutions to improve on the current situation. In turn this can result in less pressure on the climate, reduce the atmospheric pollution, while helping people to improve their well-being.

Blog 2: The ideas

15-9-2023

Part A: Brainstorming

The notes of this blog are from both our meetings on Monday and Thursday, as well as from the work session on Wednesday. Especially for part A, we try to make this difference explicit.

As we didn’t have a big idea at the end of last week, we started our meeting on Monday with that. Admittedly, we spent quite some time on what exactly the big idea was supposed to be (is it energy poverty, or a part of it?). After reading the syllabus and confirming it with a teacher, we continued with finding ideas. We were not able to make a definite choice on Monday, but we ultimately ended up with the four following suggestions. Firstly, we felt that (reducing) energy consumption would be a good Big Idea. Secondly, there was a suggestion to make the sustainable energy transition more accessible for people with low income. Thirdly, it was mentioned how poorer people can have unfair access to energy sources and services in the Netherlands. Lastly, the increasing energy inflation was found as another good idea, as it essentially forms a poverty trap. As mentioned, we weren’t able to make a choice, and extended it till Wednesday. Finally, we reflected on the first blog, finding it of decent quality. However, we think we can make it easier for ourselves by finishing blog 2 before Friday lunch.

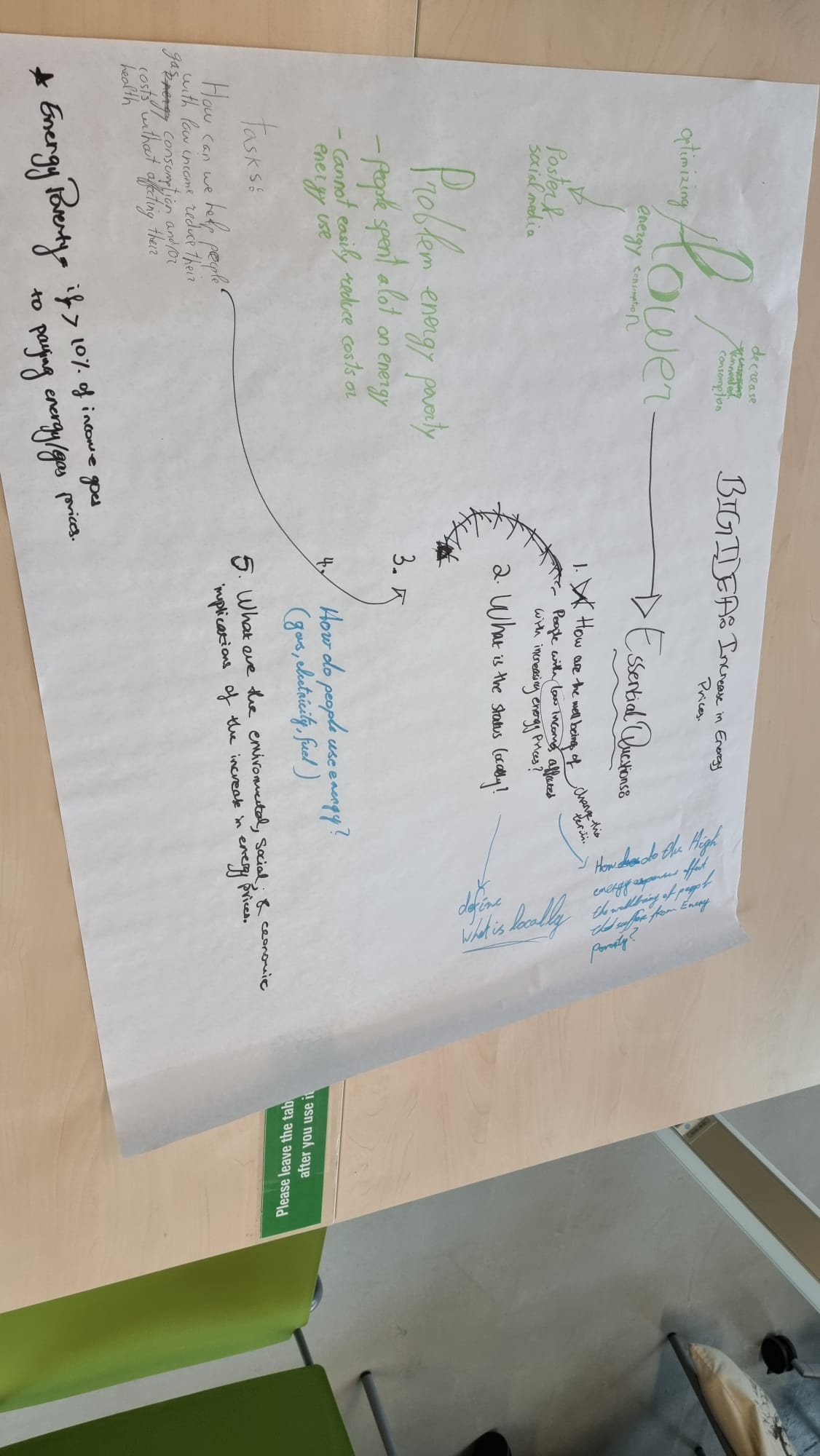

During the work session on Wednesday, we focused on deciding on the big idea, the essential questions and figuring out why they are relevant to global and local challenges.

Starting with the big idea, we have decided to keep it broad, namely the increase in energy prices.

In the Netherlands, there are very few cases where people do not have enough access to energy sources. Instead, energy poverty is caused when people have to spend a large amount of their money on energy. Following the definition of TNO, energy poverty happens when over 10% of a person's income is spent on energy costs. Looking at major newspapers, the primary cause of energy poverty is from poorly isolated houses, which cause large gas/ electricity bills. Since most of the (poorly isolated) houses use gas (CBS, 2019), our team believes that reducing gas consumption would be most beneficial. However, until we meet the stakeholder board next week Wednesday, we decided to keep it open to all energy consumption.

All in all, this resulted in our challenge being” reducing the energy consumption of people with low incomes in Twente without negatively affecting their well-being.” The last part comes from the definition for energy poverty of the EU, which argues that people suffering from energy poverty cannot just lower their energy consumption will negatively impact their (physical &/ mental) wellbeing.

Consequently, we created several essential questions (meaning we sort of did the challenge before the questions, but it worked out well for us). The first question is a literal copy of the challenge in question format: “How can we help reduce the energy consumption of people with a low income without negatively impacting their wellbeing.” Next, our second essential question is “what are the environmental, social & economic implications of the increase in energy prices”. Thirdly, we want to know how people use energy, and for what. Lastly, we desire to know “how high energy expenses affect the wellbeing of people with a low income.”

To wrap the week up, we looked at possible stakeholders for the project. Next to potential professors at the UT, we also thought of organisations that work with reducing energy costs for consumers, and a guest lecturer at the Studium Generale of last year. With that done, we divided the parts of the second blog and other action points and closed our final meeting.

Blog 2: The ideas

15-9-2023

Part B: The Problem Definition

Based on the skills readings and the lecture we had last Tuesday, the group has learned a lot in terms of constructing a research design as well as what a good research question should consist of. This was a true eye opener filled with good ideas and advice that will hopefully give the group a good push forward to start constructing research design methods as well as a sufficient research question that will help us answer and solve our challenge.

In my own words, from reading Chapter 1 of Hancke (2009), one of the important things about constructing a good research question is that the research should be relevant. What is meant by this is that the research at hand should be something people want to find out more about or something that will be beneficial for them to learn about. Maybe something that correlates with what's going on in today's world or something that is trending. The research should not be useless or out of date. In addition, people should not feel indifferent whether they find out more about the topic or not.

For us, regarding the aspect of energy poverty, and the big idea of increase in energy prices, I think that a question out of that big idea should be relevant as the increase in energy prices is something that is going on today and it has severe impacts on many households; ones that can’t keep up with this increase. Another important thing to consider is that we should really make sure that our question is not phrased as if it were a statement. The group must clearly distinguish between a question and a statement. In addition, the question should be written in a way where it can have multiple answers to it. Or in other words different opinions to what the answer may be. Another important thing was that the question should not sound or be worded too sophisticated to the extent where the reader might be confused as to what the question really is. The questions should be worded in a way where it is simple and easy to understand. The author gives a very good point where he states that the question should be easily described to our grandmothers or even at a party (Hancke, 2009).

With that being said, the group used all these important points to get a better grasp of how to structure a research question. Given that the big idea is the increase in energy prices, the group, in last Wednesday's challenge workshop decided to go with the challenge question of: Can the energy consumption of people with low incomes in Twente be reduced without affecting their well-being? We believe the construction of this question fits well with the advice Hancke gives. For instance, it is worded in a way where it could be explained to a grandmother or at a party, and it could have many answers to it.

The central research question (from the article of Middlemiss et al (2018)) would be in our own words: “how is energy poverty impacting people's lives and how are existing policies dealing with these impacts?”. This can help our question and our research as it shows the many vignettes that portray how energy poverty affects certain aspects of people's lives such as their employment opportunities and how countries respond to that by the chapter portraying to us how certain solutions are implemented and how successful they are.

Blog 2: The ideas

15-9-2023

Part C: From essential questions to global justice

When talking about how people are affected by Climate Change, the COVID-19 pandemic or economic crisis, we like to present the situation in a way that makes it seem that everyone is suffering and dealing with the same problems. However, this tends to silence the question of to what extent different people are affected by the same challenge. If you start seeing the variety of factors that contribute to problems that some of us have to cope with, then you get an idea who the victim really is.

Turning our attention to the topic of our challenge and the big idea we chose, we see that the very essence of the problem are the different conditions that every individual has to deal with. A clear example is the Wealth gap. We see that it is growing ever larger, showing that people with low income have to deal with problems that are only becoming harder to manage and new problems (e.g., the current energy crisis) that deteriorates the already unfair situation even more.

Whereas everyone is suffering from the high cost, with more individuals having to deal with financial problems and companies having to shrink or even discontinue their activities resulting in many losing their livelihoods, there are those that are not able to take care of themselves sufficiently resulting in dire conditions that can lead to health issues and even death.

And now we are still talking about the case in Europe, where we are talking about people that do have 'accessible' and reliable energy. If we zoom out we see that too many are still dealing with problems on a whole other level. As stated in last week's blog millions to billions of people lack the basic access to modern services preventing many from being able to sufficiently take care of themselves and those around them.

From this perspective we see that the principle of the wealth gap continuing to grow goes beyond the financial aspect. Individuals around the world that are already living in unjust circumstances will only see the state of things becoming worse.

To improve upon this, however, there are those with the ability to make a change by taking action. Examples are government officials that can support the people in need, such as the allowance the Dutch government is providing (Rijksoverheid, 2023). Others that can contribute are Energy service companies that can make agreements with the government, municipalities and consumers and also work with experts in the field to find more affordable alternatives and ways to reduce consumption. On a higher level, international agreements can contribute by improving the issue on a (inter)national scale. More indirectly, consumers that do have the financial means to reduce their consumption by becoming more efficient (e.g., isolating your house), changing their behaviour and becoming less reliable on energy providers to reduce their consumption and with that the demand for energy, which might better the prices.

There are drawbacks to the extent that some can help. For some, especially those in energy poverty cannot reduce their expenses through consumption as that might make the problem worse. Alternatives such as hydrogen and biofuels are not ready for large scale production, which means that as of now energy companies are limited when it comes to this approach.

Blog 3: The engagement

22-9-2023

Part A: Brainstorming

The meeting with our stakeholder last Wednesday in the pop-up classroom went really well. He told us things we never knew before and he took the lead with the conversation to spill out truly valuable insights and experiences. He began by giving his feedback to us about our presentation. He stated that in order to get somewhere with a definition of a challenge, the group had to narrow down their focus more. It was too broad. He advised us to narrow down our questions more and for us to choose and find out what exactly our challenge is that we want to solve and research. We hoped that this meeting would help us narrow down our focus a bit more.

He then gave us his own definition of what he believes energy poverty is, “relatively low-income houses with low energy labels that use a lot of money on energy”. Such low-energy houses are defined by him to be scores that are below the grade C: so D, E, F, and G houses. They pay more money as they are poorly insulated and therefore they pay the price in the cold seasons (literally). There are many solutions for such houses such as offering subsidies to houses that need the money, or giving gift cards for trading an old refrigerator, for example, with a new one, and even insulating houses for free!

These solutions sound great, but our stakeholder also told us that these great solutions don't always work. A trending problem nowadays that prevents such things from happening is that there is no trust between the people and the government. Finally, at the end, the group had some time to think about what had been said in an attempt to narrow down ideas. In short, the group narrowed down their focus to the engagement the government has with the people to improve the situation of energy-poor households. So, the keyword here is engagement. How can this be improved, and how can better trust be developed?

Blog 3: The engagement

22-9-2023

Part B: Striking Insights

As mentioned in the previous blogs and part A of this blog, we have been closely looking at the definition of energy poverty. Previously, we mostly used the idea that people suffering from energy poverty would spend a relatively high percentage of their income on energy, in line with the definitions of the EU & TNO, as well as current political discourse. It came as a shock to us that the municipality of Enschede in practice doesn’t even look at the percentage of income (energyquote). Instead, the municipality as explained by our stakeholder focuses on whether the income is within 150% of the social minimum, and whether the house labels are in the range of D t&m G.

A second insight to us was the way the national government and local municipalities (in particular bigger cities) handle energy poverty. According to him, the national government doesn’t really have a concrete policy plan in place to mitigate energy poverty, even though it forms a large part of poverty struggles of citizens, and is an essential component of the energy transition and its aims to no longer use gas in houses by 2050. In typical Dutch decentralisation politics, the government instead has made a large sum of money available, and leaves each individual municipality to figure things out on their own. On this matter, he also admitted that it's most likely that cities are wasting resources on reinventing the wheel.

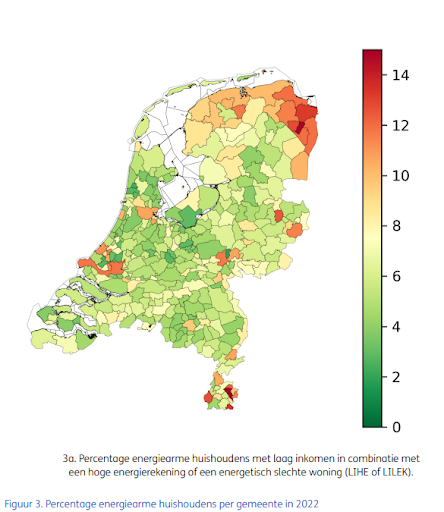

Nonetheless, we learned that Enschede actually has a pretty in-depth policy for energy poverty. This somewhat makes sense, as Enschede is amongst the municipalities in the Netherlands with the most energy poverty (image 1). This can be explained by the low average income and the amount of relatively old houses. Local policies on mitigating energy policy seem to focus on three directions.

Firstly, there is the fixed help brigade, who for free come to your house and give advice, install energy trackers and offer materials to reduce energy waste such as draft strips, cheap isolation material and water saving measures. The offside of the low costs of this policy is that the outcomes are relatively little.

The second policy measure is to give a medium amount of money as a gift card to citizens so that they can exchange their old electronics for more sustainable versions. The disadvantage of this measure (which I personally thought was genius) is that citizens don’t actually use the money for this purpose. Rather, they buy essential goods such as food and necessities for their children, or pay of depts.

By contrast, the third method was sold to us as the most effective way to reduce energy poverty (though that might also be because he himself works with that group). The municipality offers a 3000 euro budget per household to insulate their house ( the roof, floors and cavity walls) with the aim of reducing the energy label of the household to A or B. What surprises us most is that the municipality is the effort they put into making the measure as easy and low effort as possible. Information is spread through neighbourhood centres, posters and also often simply by going door to door. Ideally, the citizens don’t need to do any transactions with money or contacting companies themselves. Our stakeholder explained that this approach was done to take away distrust and break through social barriers, as the municipality has discovered that a lot of the target group either doesn’t know about the intervention methods or don’t trust them (“it must be a hoax’’).

Part C: Specific Target Group

During the session on Wednesday it came to light that the households that live in houses with energy label D, E, F, or G make up an important group to consider for the challenge. As mentioned in part A, when looking at the situation two important aspects were presented by our stakeholder. The first one is the fact that what impoverished people is the inefficiency of houses. Houses with low energy labels are a large contributor for the larger consumption, hence energy cost for households. This is why trying to use this as an approach for our challenge is something that is being seriously considered. In addition what makes it difficult to address the state of these houses is the distrust. Again, this can be mitigated by specifically targeting these households.

In addition, there is another group that can also be targeted to help work on this aspect of the problem. Neighbourhood centres (e.g. t' Proathuus) are places where people come to be part of a community, but also to get help with problems, get free things when they need it and participate in activities. Just like community centres they can provide both greater insight, as improve the relationship with the government/municipality so as to provide help. They can do this by, for example, being a (in)direct communication medium for the municipality to build connections and trust.

Part D: Big idea (and the future)

Since Wednesday, the big idea has not changed much. During the session it became clear that the scope was still too large and it was needed to find something more specific that is better manageable. Since, the big idea 'Energy consumption of households in Twente' was already focused on a relevant aspect to our challenge, the change to 'Gas consumption of DEFG labelled houses in Twente' is quite minor. The decision to look specifically at gas came partially from an earlier discussion on if energy or gas consumption should be the scope. With energy consumption an attempt was made to keep the topic broad, but now trying to narrow it down, gas was an easy decision, as it was already on the table, plus it is already clear that gas is the major contributor for the high cost.

The specific households come back to what is stated in part C about the contributing to the high expenses of households. Looking at the essential questions it is possible to say that they do not need to be changed, since they are still relevant for the revised big idea, however, it is an option to decide if the last question (What measures are currently in place to reduce energy poverty in Twente), as a result of the stakeholder that was present at the Pop-up session providing a lot of insight into the support that is available to work on the problem. Although, it is also an option to add more questions to the list rather than removing any. For example, how municipalities differ in trying to break through social barriers to speak trust and information on the previously mentioned policy measures.

Blog 4: Data Collection Plan

29-9-2023

Part A: Brainstorming & Final Research Question

On Monday we had a brief meeting where we outlined the goals for this week, created a weekplanning and brainstormed about relevant stakeholders and experts to contact for the project. Primary organisations to contact beyond our stakeholder from the municipality of Enschede were the neighbourhood centre ’t Proathuus, the TwenteBoard, Energienet and several professors at the UT. In addition, we created a draft final research question for the session on Wednesday:

“What can public organisations in the region of Twente learn from each others approach in engaging society with the intention of mitigating energy poverty through reducing the gas consumption of DEFG labelled households in Twente”

On Wednesday morning we had a second brainstorming session on the final research question. Unlike Monday, for this session and the afternoon one we were with the full group (3 people). After some discussion, we came to the conclusion that we were very interested in the 4 barriers that the civil servant from the municipality of Enschede told us during the last pop-up session. The four barriers are big obstacles that prevent more successful implementation of the energy poverty policies of the municipality of Enschede. These are, trust in the municipality/government, awareness of the help available from the municipality, the collaboration with housing corporations and the collaboration between different municipalities. Consequently, our new RQ became:

‘’What can various municipalities in the region of Twente learn from each other & achieve together with regards to energy poverty policies?”

While this question is much less detailed in its description of energy poverty, it makes the question much simpler. Ultimately, the idea behind the question is that we desire to investigate how various (big) municipalities in the region of Twente handle the previously mentioned barriers, and what their policies on energy poverty are. By reaching out to employees of these municipalities.

Work update:

On Thursday we went to the neighbourhood centre t’ Prometheus in Twekkelerveld. This is a suitable stakeholder to talk to since the municipality is working on implementing measures there now and it is one of the neighbourhoods that is more deprived. At the centre the volunteers seemed to be well aware of what we needed, however, they could not help us much with our work, so they referred us to Alifa which is an volunteer organisation that works with (mainly) seniors and one of their departments, the Fixbrigade go to peoples houses to effectuate small measures such as weather strips and radiator film. The member of that department that we were able to speak to could unfortunately only provide us with an individual perspective, since they were not able to discuss it with their colleagues in advance.

Nevertheless, we were able to get a good perspective of their work and how the department has experienced issues with trust and awareness in regards to the municipality and struggling to work with housing corporations to make a change.

Blog 4: Data Collection Plan

29-9-2023

Part B: Develop a data collection plan

The group had many meetings to brainstorm and conclude on a challenge as well as on our research question which we have finally used well to achieve a clear plan of what is to come for the Investigation phase and possibly the Action phase.

With these meetings came a lot of brainstorming, which also led to implicit implications of how we can go about collecting data. Even from the very beginning when the group was just constructing their big idea, we had always mentioned possible ideas of how we could get information, who to interview, and so on. However, the ideas were never really concrete and they had never really been constructed in a well-organised plan, of what to do, who would do what, and when will what be finished. In addition, the group never thought of essential questions like which data-collecting methods would suit which questions. Not until last Wednesday’s workshop session at least.

Last Wednesday's workshop session was the first baby step the group took to think about our data collection plan. This was because the workshop consisted of us trying to think of how each of our guiding questions would be answered and how the data for these answers would be collected.

Although I believe more could have been done in terms of productivity, this was a beneficial workshop for the group. We came up with some good ideas, like mapping out our stakeholders. This would give us a good start in terms of the data collection plan because we have somewhat of a map of our stakeholders that could help us find out how they relate to each other, how they can be used together (or alone) to gather data, and which stakeholders are most suitable to get answers for which questions. The group thought of interviewing stakeholders to get their answers to some questions like: How does the municipality of Enschede mitigate energy poverty? Or a question like: What is the perspective of municipalities in Twente on collaborating on mitigating Energy Poverty?

In addition to the interviewing of stakeholders, the group also wants to conduct desktop research such as the reading of articles, literature reviews, and many more to have an idea of what secondary research offers and how that could be used to either help the generation of questions and ideas when it comes to interviewing stakeholders or to gather data to answer our guiding and essential questions to our research question. An example of one question that could be answered by secondary research would be: How do other big municipalities in the region of Twente aim to reduce energy poverty in the region of Twente?

The group also discussed some things with the tutor that were beneficial, and one of them was that the group needs to consider quantitative data in addition to qualitative data collection that would be generated from interviews. Therefore, the group will not only interview stakeholders, but for the sake of time, effort, and quantitative data, the group could send out surveys to stakeholders to generate numerical results to some questions that would help answer our research question.

To conclude, the last workshop gave us the first push to generate a data collection plan, and we now have a good idea of how we will go about doing things. Still, there are things left in our plan to discuss, such as what types of data collection will be carried out by whom and when will things be finished.

Blog 4: Data Collection Plan

29-9-2023

Part C: Systemic failure & Systemic Change

The system that this part speaks about is defined as energy poverty in the region of Twente (Overijssel). First, we should first look at the general characteristics of the system. Relatively speaking, the population density of Twente is low compared to the Netherlands. In addition, Most of the population is centred in the municipalities of Enschede (160.000), Hengelo (75.000) and Almelo (75.000). The remaining population is spread amongst rural areas, often in large old houses in small villages and cities. Consequently, these households are poorly insulated and pay relatively much for their energy consumption, thus facilitating energy poverty.

Another important component of energy poverty is that we only recognise the problem since energy bills increased massively in the months before the Russian-Ukraine war in 2022. Energy poverty has only been on the political agenda as a real problem for the last 2.5 years (energy crisis). As a result, there is no real national policy plan to tackle the problem of energy poverty within the Netherlands. Instead, the government has almost literally dumped 300 million on the municipalities and told them to figure things out.

This leads to one of the first barriers preventing system change, namely the lack of cooperation between municipalities with regards to the mitigation of energy poverty. As mentioned in the previous blog, the stakeholder who worked for the municipality of Enschede explained that there was little contact between different municipalities, even in the same region. Consequently, he considered it likely that ‘the wheel is reinvented often’. Secondary sources such as students from our class (with parents working for an energy consultancy for example) indicated similar experiences.

The second barrier identified that is currently causing some form of system failure is the lack of trust in public institutions. Due to a multitude of scandals where citizens were ignored, discriminated against and treated unfairly without due cause, there has been a rising distrust against the Dutch government. Next to the national subsidy scandal and the earthquake damages in Groningen, the way citizens in Almelo were treated after their houses sinked due to the deepening of a nearby canal has eroded support in the province of Overijssel. Combined with the focus of the Hague on the “Randstad '' over the “regio” and scepticism after Covid, it leads to some people no longer believing that energy poverty subsidies are real.

That is of course assuming they even are aware of them in the first place, hence ‘awareness’ is the third barrier we have identified as a factor limiting system change. This mainly refers to the fact that many citizens are unaware of the measures offered by local governments to limit climate change. This is for several reasons, including the diversity between municipality approaches, the stigma around poverty, and the fact that the interventions created are very new. For example, the fix brigade of Alifa, a local volunteer organisation working with the municipality of Enschede, has only been created since May 2023. Obviously, it is also important to spread awareness on the importance of mitigating energy poverty through lowering gas consumption for the net-zero society, but this is a lesser problem compared to the lack of knowledge from citizens on how they can quickly and effectively lower their energy consumption.

The fourth barrier preventing effective insulating of DEFG households to reduce their gas consumption are the housing corporations. Similarly to the lack of cooperation between municipalities, this is more of a synergy opportunity as much as a barrier. The reason for this lies within the complexity of the housing market in the Netherlands. Housing corporations, house owners and other organisations all have their own little dots in an ocean of colours, which means that effective cooperation between all parties is extremely important for a smooth insulation process. However, housing corporations generally have their own set plans on when they want to insulate (and renovate) their houses. While there is some communication between them and other actors in the energy poverty system of Twente, it is far too little. One possible idea offered by Alifa was for housing corporations to spread information on free measures of the municipalities, such as fixed brigades and so on.

All in all, the previously mentioned 4 elements do not necessarily cause system failure, but they do function as a barrier preventing the synergy needed to create system change in the energy poverty system of the region of Twente

Blog 5: Looking Towards the Future.

13-10-2023

Part A: Stakeholder Interviews

We started our week with an interview with assistant professor Sikke Jansma of the University of Twente. He is an expert on stakeholder engagement in the energy transition, in particular with the societal elements such as communication and trust. In addition, he has been involved with a pilot project to get the Twekkelerveld neighbourhood of Enschede of natural gas.

He argued that energy poverty was a hindrance towards the energy transition of the Netherlands. To take households off the gas grid, they must have an energy label of C+, but a lot of households and energy corporations don’t have the money to increase the energy label like this. In the short term, he expresses that the national government doesn't provide enough money for all stakeholders to effectively insulate all households, unless they increase the rents for example. On the long term, where the net-0 society is the end goal, infrastructure needs to be changed together with individual behaviour and the energy labels, resulting in even higher costs. In comparison to our interview with the volunteer organisation, he was confident that housing corporations would want to insulate houses, but they just don't have the capacity or money.

He suggested several solutions, though we didn't find them very likely or convincing. First, Citizen Led Initiatives and Bottom up policy were suggested. One example of an benefit of these would be that they are inclusive towards all citizens. On the other hand, doing a societal transition from the bottom up is not very structured or likely. It can also result in many different approaches per energy region, resulting only in a big mess for the national government to solve. Other solutions include that the municipalities and the region take on an facilitating role, and the usage of social ambassadors and energy advisors to increase awareness and trust. However, based on our conversations with public organisation representatives, energy poverty is a far too big problem for the municipality to take on anything less than an active role.

On Wednesday during the pop-up session, we also had an interview with Niels Busschers, who sits in the municipality council of Borne and works on the energy transition for the municipality of Haaksbergen (24000 inhabitants). He explained more about the SPUK subsidy budget, and how most of it comes in different rounds. In addition, most of the budget is gone, meaning that for now any plans on mitigating energy poverty through the SPUK is unlikely to be very effective. Furthermore, he argued that the most important thing to reduce energy poverty through any government intervention is to simply spend the money as fast as possible. The reason for this lies in the bureaucratie of the Netherlands and public organisations in general. The majority of any such money goes to consultancy and administration, so it is better to burn the money on something that is likely to work than to use a portion of the subsidies on something that is sure to work. Here, different municipalities struggle with different problems. Smaller municipalities (<50.000) simply do not have the data nor the capacity to always know and be able to make full use of the designed government interventions. In the case of Haaksbergen, all money was simply used on buying solar panels for around 2% of the households. Bigger municipalities on the other hand are much less flexible as an organisation, and also slower. Before any local policy can be implemented, long discussions in the municipality council are likely to frustrate the process.

Blog 5: Looking Towards the Future.

13-10-2023

Part B: Pop-up

The data that has been acquired till now has been very interesting (part C will elaborate on this). The most striking knowledge that we have gained is how the government is trying to handle the problem. Their approach to leave it up to the municipalities to mitigate it. The government has mainly been giving financial support, but is lacking to provide other forms that municipalities are in need of. Many municipalities are what we have been referring to as ‘reinventing the wheel’ with little collaboration with other municipalities and government organisations. While our team was partially already aware of this fact, the conversation with Niels Busschers from Haaksbergen made it more clear what this could mean financially for a municipality. One possible solution discussed which had his agreement was the design of a data-base with existing solutions.

Blog 5: Looking Towards the Future.

13-10-2023

Part C: Remaining Data Collection

Until today, our team has spoken with four stakeholders (two municipalities, a researcher and a volunteer) about the situation of Energy Poverty, what is being done about it and what hurdles still need to be overcome. The data collected from these engagements has been focussed on effectiveness of measures, knowledge and attitude of people suffering from energy poverty and the interaction of stakeholders in the context of Energy Poverty and transition.

What has been a recurring topic is the limiting factor of households that can be helped by the municipality of Enschede. Three variables have been contributed to that are the awareness of people that these measures are there, the trust they have in the municipality to help them and the collaboration with housing corporations to coordinate implementation of measures. What has become evident is that collaboration between stakeholders is something that still yields potential. This has been our main focus during the investigation. However, another point has come forward later in the investigation.

More specifically, the different levels at which stakeholders interact has been a topic since the start of this stage and has only become more present as an issue over the course of this phase. To elaborate, Energy Poverty is mainly dealt with on a local level (by and in the municipalities). The poverty aspect of Energy in this country is not being handled as the rest of the Energy developments that are happening now. The Energy transition is now being set in motion on various levels ranging from local all the way to the national level.

In the coming time, two more interviews will be held that will provide us with a more holistic view of the situation. This will give us an expert perspective on Energy Poverty and the perspective of the housing corporations to the main problem. This will provide understanding that fills some gaps in the exploration of the challenge. Furthermore, the lack of central action and collaboration is a perspective that needs to be turned to, before a decision for the mitigation becomes clear. Unfortunately, the limited means that are available to our team might mean that the choice has to be made sooner than hoped.

Blog 5: Looking Towards the Future.

13-10-2023

Part D: Possible Solutions

So far, after many sessions of data gathering and stakeholder interviews, the group has reached two possible solutions or directions in answering the research question, “What can various stakeholders in the region of Twente achieve together with regard to energy poverty measures?”. After our pop-up session yesterday, in addition to the interviews we have conducted so far, we have started to get better ideas of possible directions to solve this research question. Also, the PESTLE analysis helped us determine a solution, because it showed how the addition of the drivers, in each category, contributes to a possible answer and shows how a solution could aid or impact these characteristics. These characteristics refer to the dimensions of the PESTLE analysis (Political, Environmental, Social, Technological, Legal, and Economical).

For instance, a possible solution was first constructed by considering the Energy Transition regulation, which was a driver in the Political section. We then connected that to another driver, Insulation, which was in the Technological section. They were connected because we realized that one of the goals of energy transition is to reduce energy consumption and to make it more efficient, especially in households. One of the ways to achieve that would be to insulate the houses.

However, many people who live in social housing, cannot make this decision by themselves, as they either do not have the money for it or it is the housing corporation that makes these decisions. If such a decision were to be made by the housing corporation, rent would increase for the tenants, which would be something that they would go against since most of them do not have the income to meet such expectations. This helped us to look into the Social section of the PESTLE analysis, more specifically linking what has been discussed to the drivers of income and human health. Finally, the solution was to link a lot of that to the legal and political sections, such as the municipalities, because they could help by providing subsidies to make this change happen. In simple terms, a solution would be to make the municipalities of the Twente region provide subsidies to help install insulation in housing corporations because that would aid the financial situation of the tenants, and lead to more efficient energy consumption, therefore a start to the energy transition goal of the country.

Blog 6: Designing and testing your solution.

13-10-2023

Part A: Solution

In the first phase of the research we established that the main barriers preventing more optimal measures to reduce energy poverty in the region of Twente are the lack of trust, awareness, data, national support and money. In the second phase of the research, we want to establish how the cooperation between stakeholders in the region of Twente can weaken these barriers, leading to more effective mitigation of energy poverty. Objectively, the lack of money is not something we can do anything about in this project. However, for the other barriers, we recommend some forms of cooperation to be within their own groups of stakeholders, such as a broader alliance between housing corporations and a database for energy policy interventions of municipalities, while others are cross stakeholder groups, such as neighbourhood projects.

In all cases, the main idea is that cooperation between stakeholders prevents scenarios in which individual stakeholders are all trying to solve the same problem on their own. Concretely, that means that stakeholders share their methods of spreading awareness of their policy measures, strategies on how to convince suspicious/ doubtful citizens, gather data in a quicker and cheaper way (instead of mass using consultation companies), or how to make optimal use of the government subsidies.

During the desktop research, it was found that around 70% of all households suffering from energy poverty live in social housing. Therefore, it is essential that housing corporations reduce the gas consumption of houses, by making them more sustainable (improving the energy label) through insulation and other energy saving measures. Based on the interview with employees of Welbions & WoON Twente, the main issues were money, the difficulties of government subsidies and people lacking trust in the financial benefits of proposed measures. In line with the opinion of WoON Twente, we propose that the final two issues can be improved through more intense cooperation between housing corporations in the region of Twente, as well as through alliances with other regions. Advantages of this include that housing corporations can make use of each other's network, share knowledge of the best contractors, buy required resources in bulk (if necessary), share plans on how to best convince tenants, and possibly pool money for mutually beneficial research, consultation, or other expenses.

Currently there is already cooperation between housing corporations in the region of Twente through the alliance of WoON Twente, which has 17 housing corporations. We propose that housing corporations from the remaining four municipalities are contacted, existing cooperation is intensified (though we lack information on how to concretely do this), and connections with other regional alliances are started.

For the municipalities, we propose to create a database of existing energy policy interventions and programmes, to reduce the costs of “reinventing the wheel”. In addition, a relationship that mutually benefits bigger and smaller municipalities could be created, where bigger, richer municipalities provide access to important energy poverty related data, while smaller more flexible municipalities share their tested ideas.

By using this database, municipalities and other organisations in the region of Twente should be able to get an overview which energy poverty solutions are most suitable in their specific context, for example based on available budget, amount of people helped, support from society, and so on. The database will show various items such as datasets, reports, energy policies and more. For the items general information will be included to make it easier for the user to find what they need. This information will be: title/name, description, date of publication, author and contact person. Similar to other database search engines, the user can search using keywords and filter the items on aspects like year of publication, municipalities and type of documents AS a last part, the website of the database will include an overview of ongoing projects and collaboration, show information on the nature of collaboration, description of projects, status of the work and contact information.

Other ways of cooperation are through integrated neighbourhood projects, where the complete renovation in line with the energy transition is planned for an entire neighbourhood at once. However, this method is still in its pilot phase, and proves to be particularly difficult due to the amount of stakeholders involved, as well as the complexity and broadness of the addressed changes at once (going off gas, maintenance of sewers & pipes, making houses more sustainable).

One final suggestion of possible cooperation is through Citizen Led Initiatives/ Renovations and local energy communities, as this has some academic support and was mentioned in the interviews with the professors. However, it is still vague for us, and we need to spend more time on making this form of cooperation more concrete.

Blog 6: Designing and testing your solution.

13-10-2023

Part B:

Designing the provotype has not been easy. The reason for that was because there were a lot of brainstorming sessions that led to new directions and new ideas in the last weeks of the action phase. Each time we feel like we have reached a consensus, we develop ideas further and realise limitations or improvements to our previous solution. We were told such things could happen when starting out with the project by our tutors, however, this becoming a reality so late in the project was something that was a bit frustrating. However, this was not always something bad, because it led to more concrete and better thought prototype ideas. Therefore, something that could be improved, would have been to prioritise generating a prototype idea from more of an earlier stage, and investing time and effort together to develop a well thought out prototype idea together, without any possible shortages, as I do feel the construction of our prototype was a bit rushed, and more time would have been beneficial for the group.

Looking back, the best thing we’ve done was the amount of interviews conducted. I feel like as a group, we have truly taken advantage of conducting interviews with important stakeholders more than any other group and that resulted in really valuable insights that helped shape our understanding of the topic and of possible solutions.

Part C:

Since our prototype is still being developed, testing of the idea has not yet taken place. Once we have prepared the idea sufficiently, we are planning to share our mockup of the website, with our contact at the municipality of Enschede and Haaksbergen. This initial data on the prototype will give an idea if any changes have to be made before the Pop-up session and the attitude of stakeholders on the solution. Their response will also provide insight into the willingness to adopt the system and help indicate if active promotion of the database is necessary to get stakeholders to participate. We expect an overall positive reaction, perceiving the database to have potential to mitigate some aspects of the problem, however, there will be questions on the execution and comments on details of the information available on the webpage.

Part D: Outline what still needs to be done before the exhibition on Nov 6

(1200 words altogether, also include visuals, sketches of the prototype,

What still remains, is the finalisation of all possible prototype ideas, as well as testing the idea and generating data from the feedback given. In addition, we are also currently finalising the platform for the municipalities, which is one of our main solutions. This is the prototype that will be tested, and it is a platform where the targeted user are the municipalities in the Netherlands, and they can view ongoing projects being conducted to mitigate energy poverty, as well as a database filled with useful information about the current state of energy poverty, results of projects, conclusions, drawbacks, and even predictions.

Visual WoON Twente